Before you get the wrong idea, this article is not about English.

It’s true that English is dominant on the web. Maybe half the web is in English.

But that’s not what I mean when I say that the web is written in the wrong language.

It wouldn’t matter if the web were written in Spanish, Swahili or Sanskrit, it would still be the wrong language.

The web shouldn’t be written in any language spoken by humans.

It shouldn’t mimic the way we speak.

It should mimic the way we think.

—

If there’s one thing that gives us humans an edge over other species, it’s thought.

It’s right there in the name of our species: homo sapiens. We humans think.

But there’s a problem with each of us thinking.

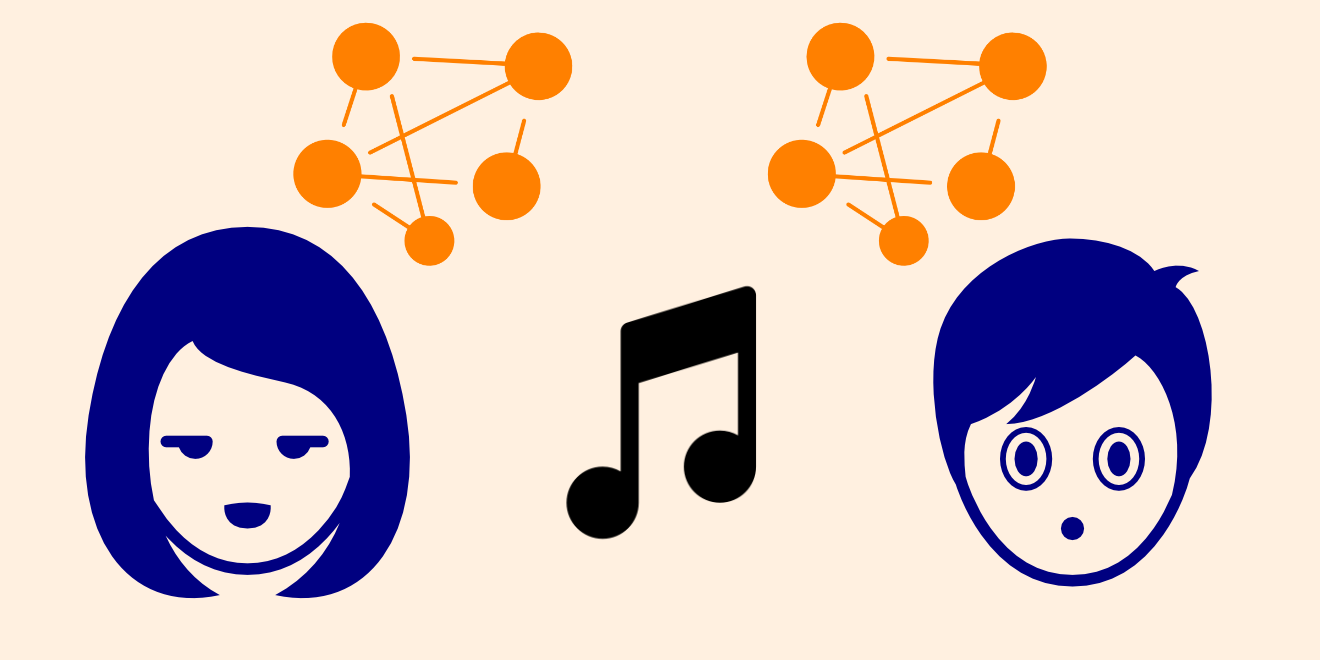

In our brains, a hundred billion neurons are intricately interconnected, capturing complex ideas, firing brilliantly with every thought.

But all this activity within each of our minds wouldn’t give us such an edge if we weren’t able to communicate our ideas from human to human.

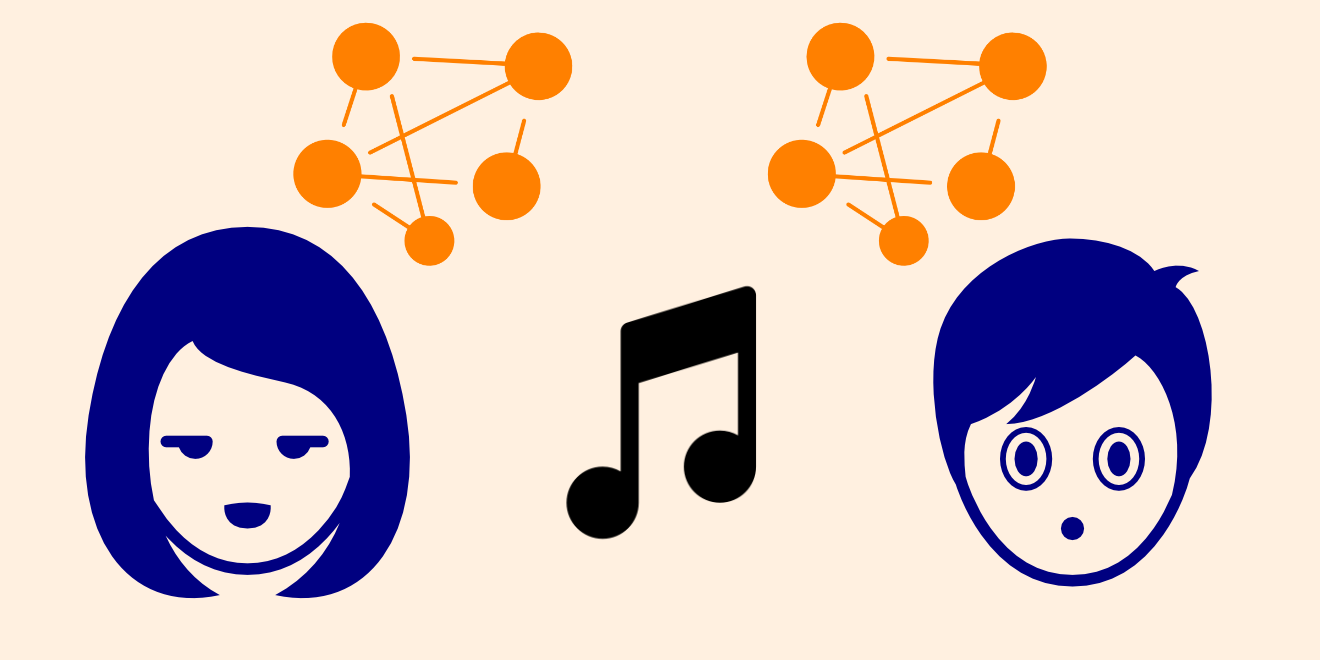

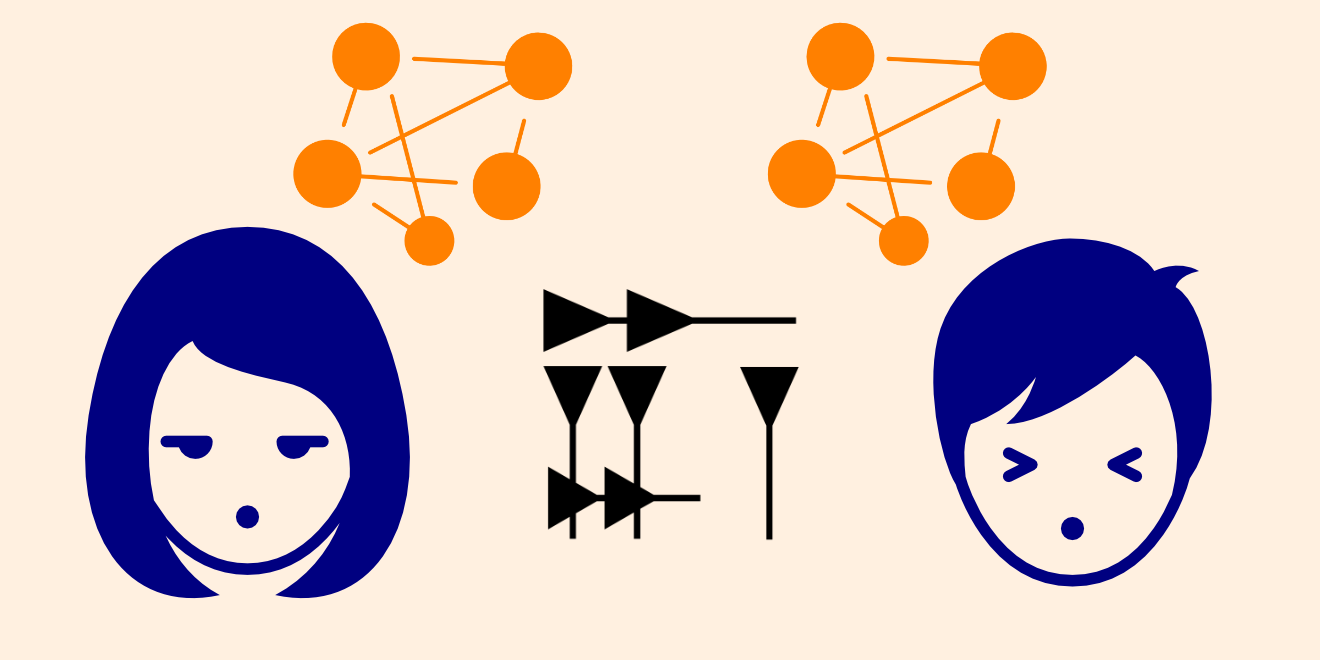

How do you take complex ideas, encoded in this hypergraph inside our heads, and communicate them from one mind to another?

Hypergraph to glyph

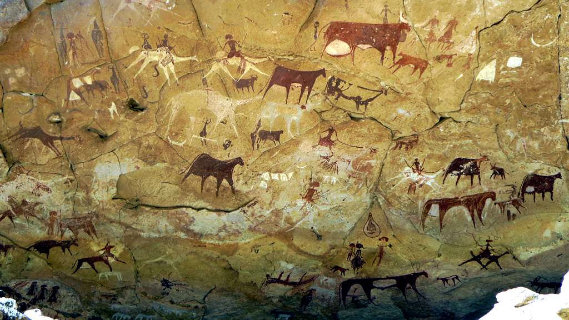

A few tens of thousands of years ago, we came up with an answer to this question.

Language.

We translated our ideas into phonemes, expressed as sounds in our larynxes, sounds that could propagate a few yards through our planet’s atmosphere from human to human, sounds that could be received in our cochleas, interpreted as phonemes and translated back into ideas.

It’s a slightly overcomplicated way to communicate ideas from one mind to another, but it worked.

Boy, did it work.

Hypergraph to glyph

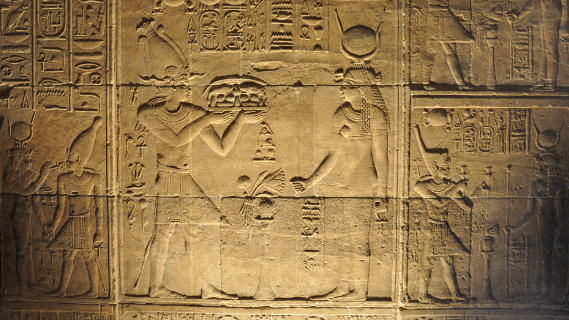

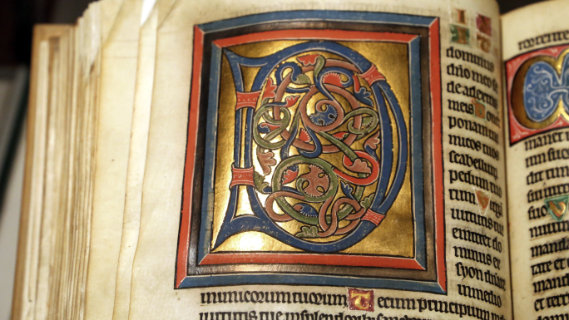

Then, a few thousand years ago, we started expressing those phonemes not as sounds, but as symbols, pressed into clay, carved into stone, inscribed on papyrus. We invented writing.

It’s still a slightly overcomplicated way to communicate ideas from one mind to another, but it worked, not merely over a few yards, but across continents, across centuries.

Boy oh boy, did it work.

Hypergraph to ASCII

Then, a few decades ago, we invented the web.

The internet can do way more than a tablet of clay, a block of stone or a scroll of papyrus. Rather unimaginatively, however, we invented a web that’s based on that same overcomplicated system we started using all those tens of thousands of years ago.

Language.

Go to any web site, and you’ll find it’s written, maybe in English...

...maybe in Japanese...

...maybe in Arabic...

...but in any case, in a language.

Language is a slightly overcomplicated way to communicate ideas through our planet’s atmosphere.

Language is a slightly overcomplicated way to communicate ideas through clay, stone or papyrus.

But seriously, language is a mind-numbingly overcomplicated way to communicate ideas over the internet.

We can do better than this.

Nothing lost in translation

The over-complication here is in the translation of ideas into phonemes and back into ideas.

Why don’t we just skip the translation?

I mean, we couldn’t skip the translation when we first started using language, all those tens of thousands of years ago.

We couldn’t directly represent the ideas in our minds – all those intricate interconnections between neurons – as sounds propagating through the atmosphere. That would have been asking too much of our larynxes.

Nor could we skip the translation when we first started using written language, thousands of years ago.

We couldn’t directly represent the ideas in our minds – all those intricate interconnections between neurons – as glyphs in clay, in stone or on papyrus. That would have been asking too much of our styluses, chisels and quills.

But today, we can.

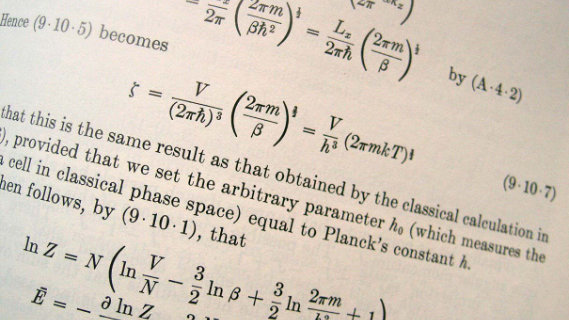

On the web, we can directly represent the ideas in our minds – all those intricate interconnections between neurons – as a knowledge hypergraph.

Instead of translating the ideas in our minds into characters when we write web pages, only to translate them back into ideas in our minds when we read those web pages, let’s skip the translation.

I’ll say it once again.

On the web, we can directly represent the ideas in our minds – all those intricate interconnections between neurons – as a knowledge hypergraph, on our screens, in virtual reality and in augmented reality.

That’s what Open Web Mind is all about.

Let’s go beyond the ums and ahs formed in our larynxes, beyond the ASCII character set, beyond language, to a more powerful way to communicate ideas on the web, with nothing lost in translation.

Subscribe to the Open Web Mind newsletter to be the first to know more.