Why is it so hard to flow from one thing to another on the web?

In our minds, we flow so easily from one motion to the next...

...one feeling to the next...

...one idea to the next.

Why can’t it be like this when we’re on the web?

Why can’t we flow as easily through our collective mind?

Well, with Open Web Mind, we can.

—

You know what I mean by flow, right?

When we’re absorbed in a task, whether it’s manual or purely intellectual, our minds fire smoothly, like well-oiled machines.

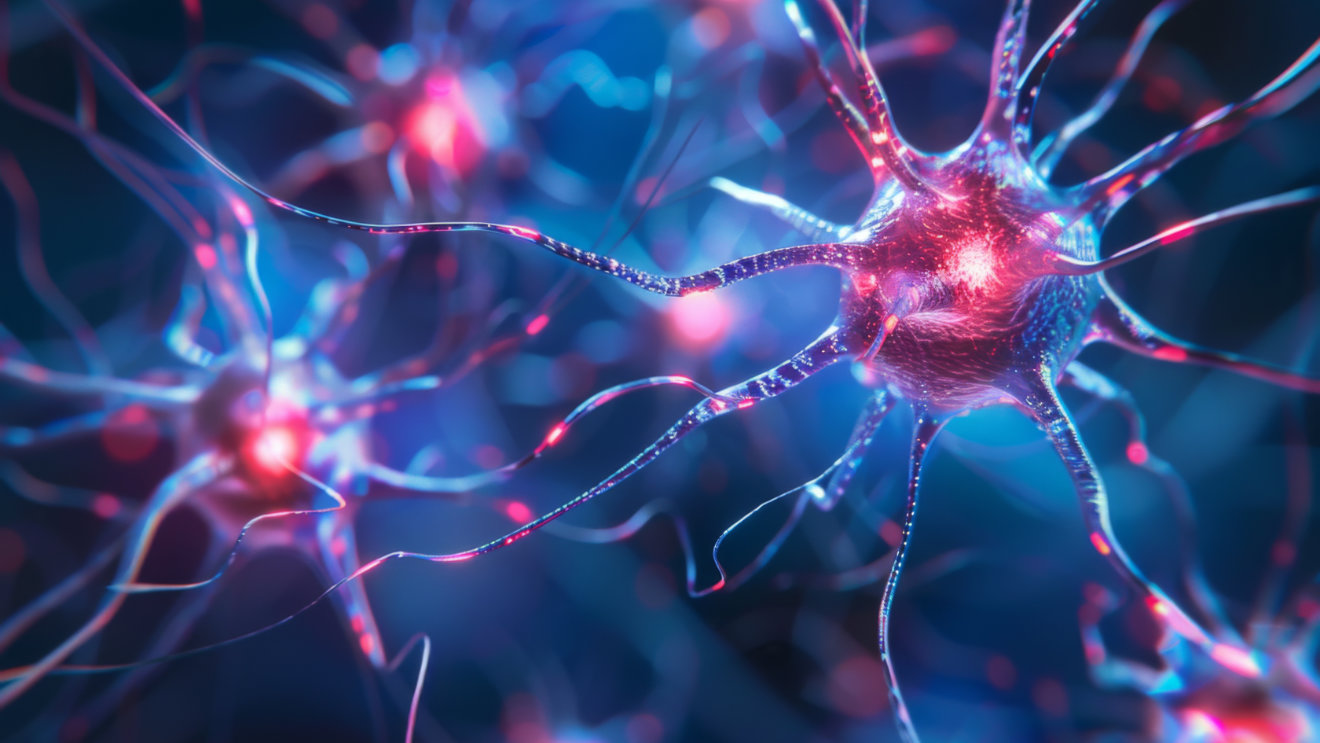

It’s no surprise that we’re capable of such flow, given the way our brains are connected.

When one neuron in our brain fires, a signal is transmitted along an axon and across synapses to the dendrites of other neurons, which fire in turn.

The transmission of these signals along learned pathways through our brains allows us to flow with ease and expertise.

Our tools allow us to extend such flow beyond our bodies.

Watch a mechanic...

...a violinist...

...or a skier...

...and it’s hard not to see the wrench...

...the bow...

...and the poles...

...as part of the person.

Cycle across town...

...or drive across the country...

...and you feel the flow of your mind extend into your bicycle or your car.

Flow can even extend into our computers... well, sometimes.

I can lose myself in the task of writing an article...

...or editing a video...

...my computer extending my creativity.

But when it comes to exploring knowledge on the web, flow is the last word I’d use to describe my experience.

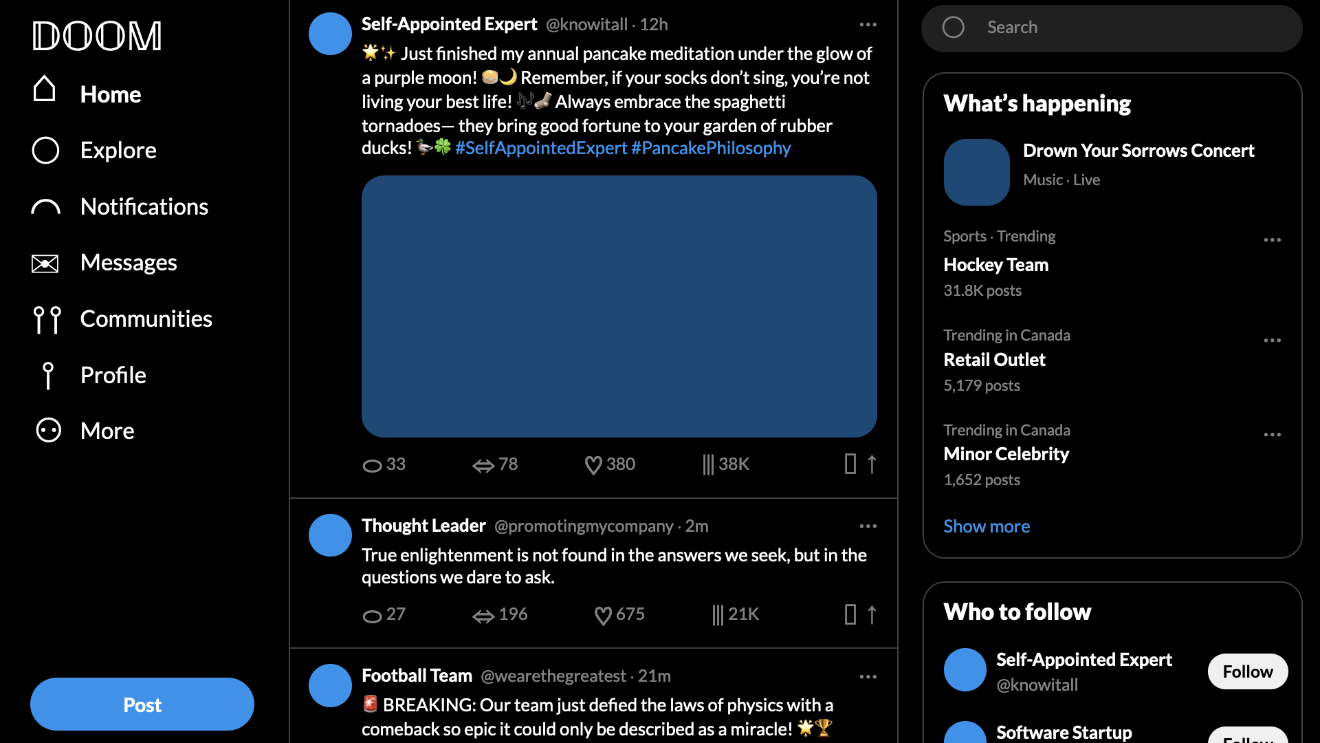

Infinite doom

Take TikTok, Instagram or X.

These platforms serve an endless stream of videos, images and messages.

Such infinite scroll is the opposite of flow.

For one thing, there’s no branching.

The signals in our brains can branch from one neuron to thousands of others, and from those neurons to millions of others, and from those neurons to billions of others.

Scrolling on TikTok, Instagram and X, on the other hand, takes you from one video, image or message to the next one, and the next one, and the next one, and so on along a one-dimensional furrow.

For another thing, there’s no agency.

In our brains, we decide where we go next.

On TikTok, Instagram and X, the algorithm decides.

Looking for links

Or take Google.

When you’re searching on Google, you tell it what you’re searching for.

Google gives you a bunch of ads followed by a list of links.

You click on one.

If it proves not to be what you were searching for, you come back and click on another.

Barely any branching.

Barely any agency.

This is not flow.

Questionable intelligence

Or take ChatGPT.

When you chat with GPT, you ask it a question.

ChatGPT tells you the answer.

It might be a bit preachy, it might be a bit patronizing, it might even be delusional, but it’s an answer.

If it proves not to be what you were asking, exactly, you ask a follow-up question.

Barely any branching.

Barely any agency.

Again, this is not flow.

Tangled web

Even on the open web, where you can follow links between pages, it’d be a stretch to describe the experience as flow.

Sure, you can branch. Each web page links to tens or hundreds of others, and those web pages link to hundreds or thousands of others, and those web pages link to thousands or tens of thousands of others.

Sure, you have agency. You can choose which of those links to click, which path to follow through the web.

But it’s far from effortless.

Every time you arrive at a web page, you have to dismiss a bunch of pop-ups, ignore a bunch of distractions, and start reading, one-dimensionally, from the top of the page on down.

Somewhere in that chaos of pop-ups, distractions and words, you might find a link to a web page you’d like to visit next.

But it’s about as far from the firing of neurons in the human brain as you can get.

It’s not reflexive.

It’s not smooth.

It’s not flow.

Flow follows fire

In Open Web Mind, I’ve set out to make flow exactly like the firing of neurons in the human brain.

Open Web Mind is a hypergraph of nodes, representing ideas, and edges, representing the connections between those ideas.

You can flow from node to node along the edges.

In other words, you can flow from idea to idea along the connections between them.

Armchair travel

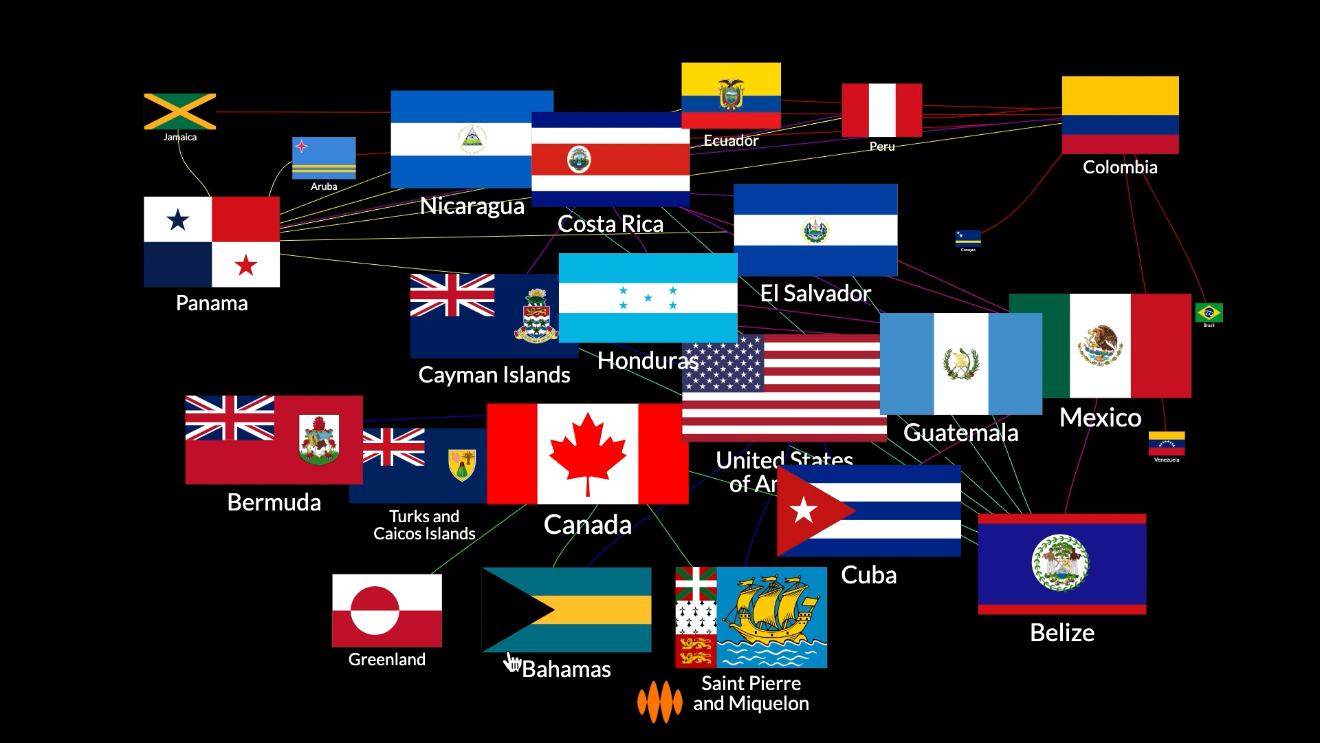

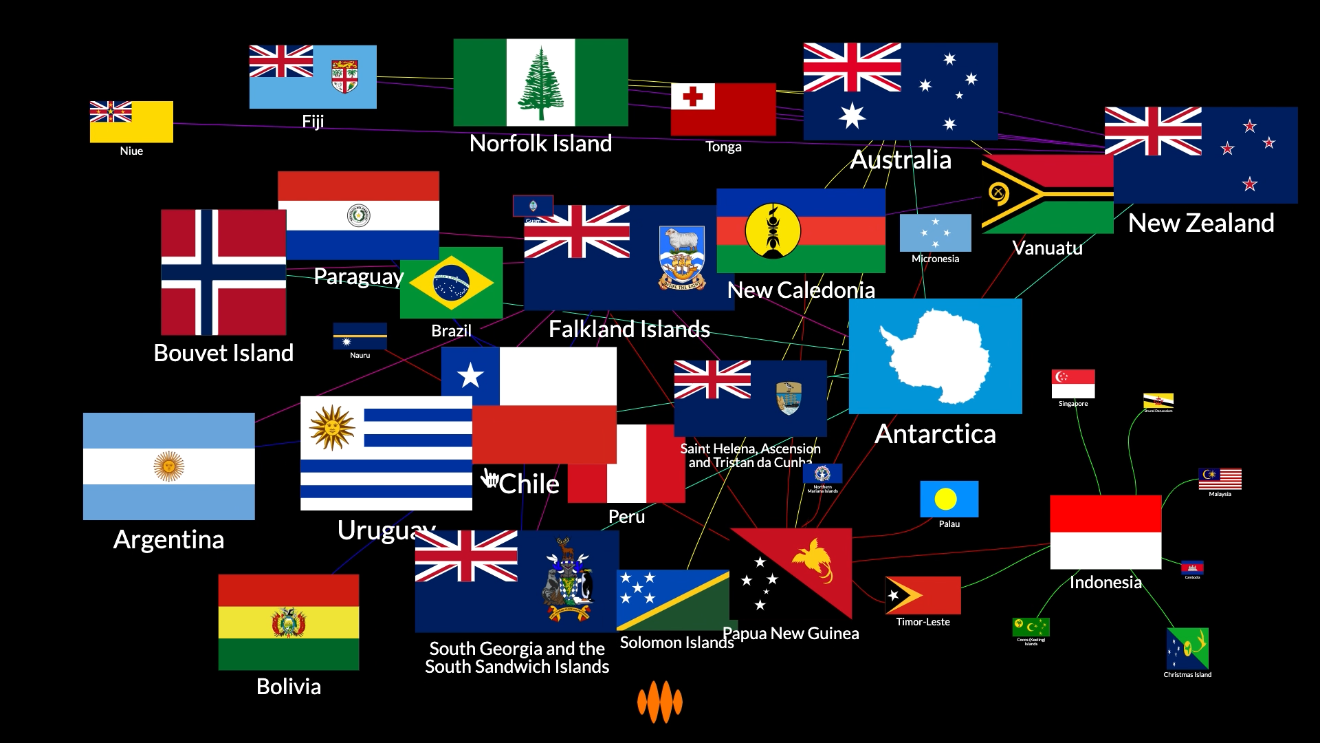

Here’s a mind in which the nodes represent the countries of the world, and the edges connect countries that share a land border or whose capitals are relatively close to each other.

I’ll start with Chile.

You can see that it’s connected most strongly with Argentina, with which it shares one of the longest land borders in the world. But it’s also connected with other countries in the southern part of South America.

Now I’ll flow to Brazil.

That brings to mind more countries, ones that are close to Brazil, in addition to the ones that are close to Chile.

Let’s keep flowing north, via Columbia, Panama, Costa Rica, Belize, Mexico and America to Canada.

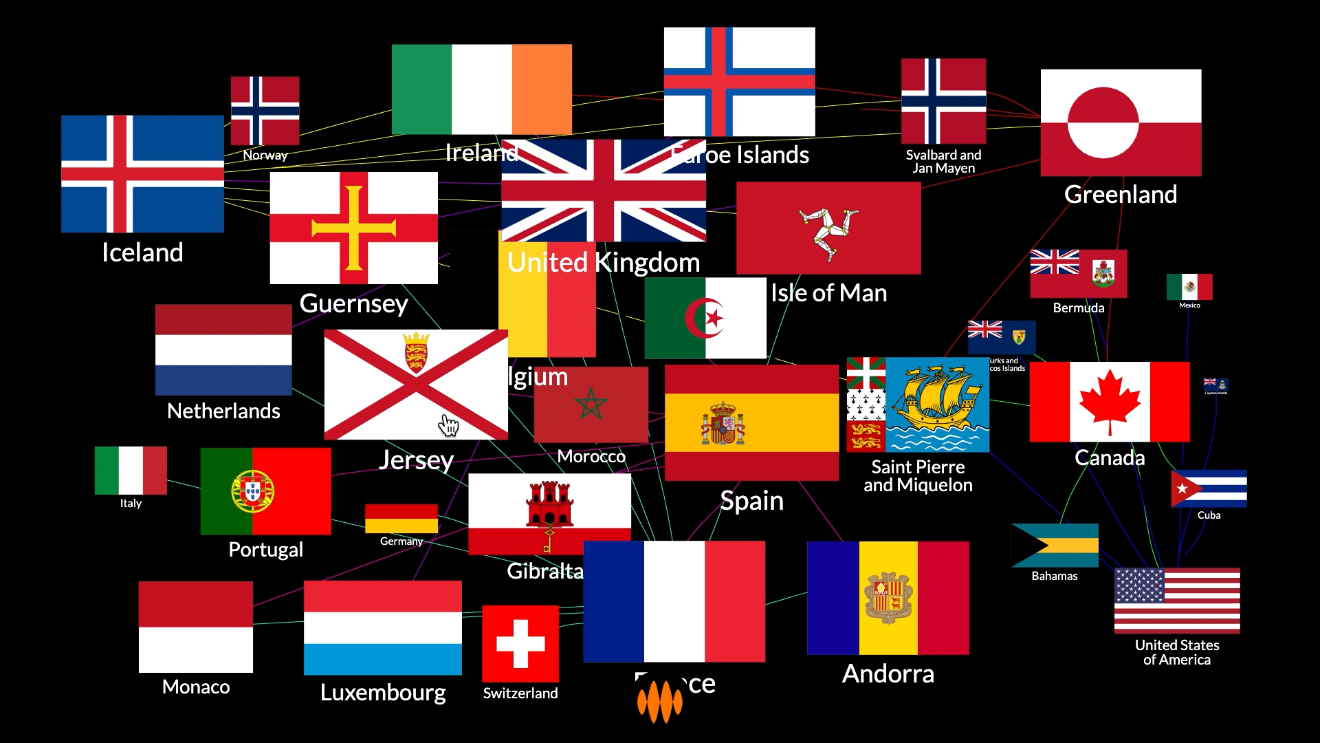

Now let’s hop across the Atlantic, via Greenland and Iceland to Britain, France and Spain.

Now across to Africa, via Morocco, Algeria, Libya, south through Sudan, Ethiopia and Kenya, to Tanzania, Mozambique and Madagascar.

We’ve come this far, so let’s carry on around the world. Across the Indian Ocean: Seychelles, Maldives, India. Through Southeast Asia: Burma, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia.

Papua New Guinea. South again: via Australia and New Zealand to Antarctica. Finally, a quick stop-off in the Falkland Islands and back to Chile.

Elementary, my dear Watson

The connections between countries I just used to circumnavigate the globe are spatial, but connections can also be purely conceptual.

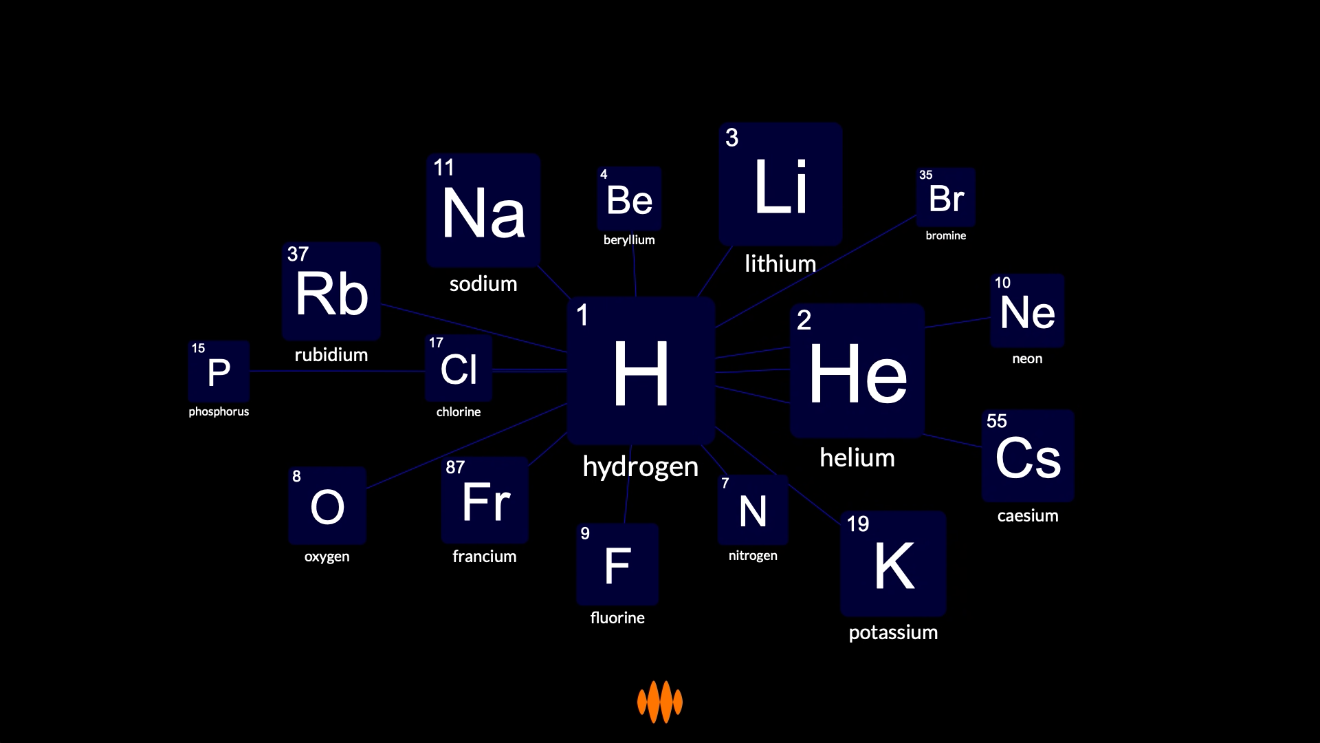

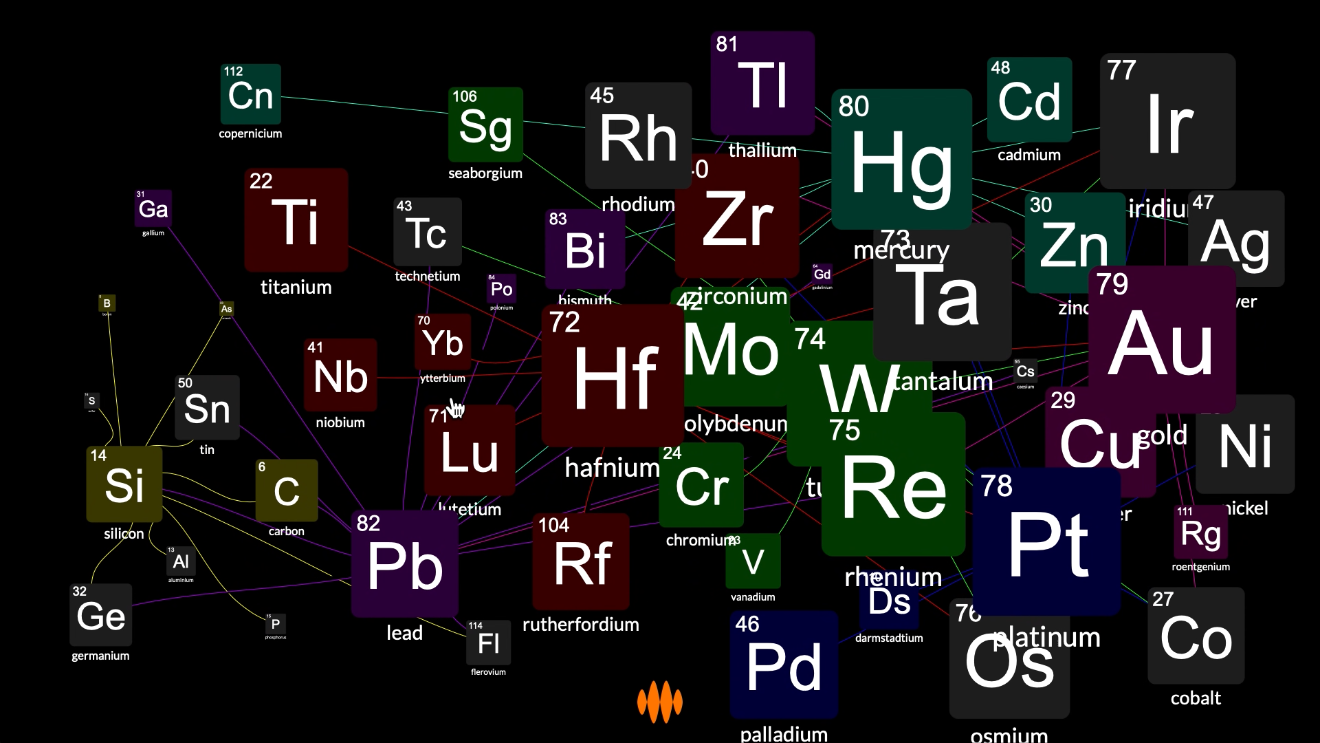

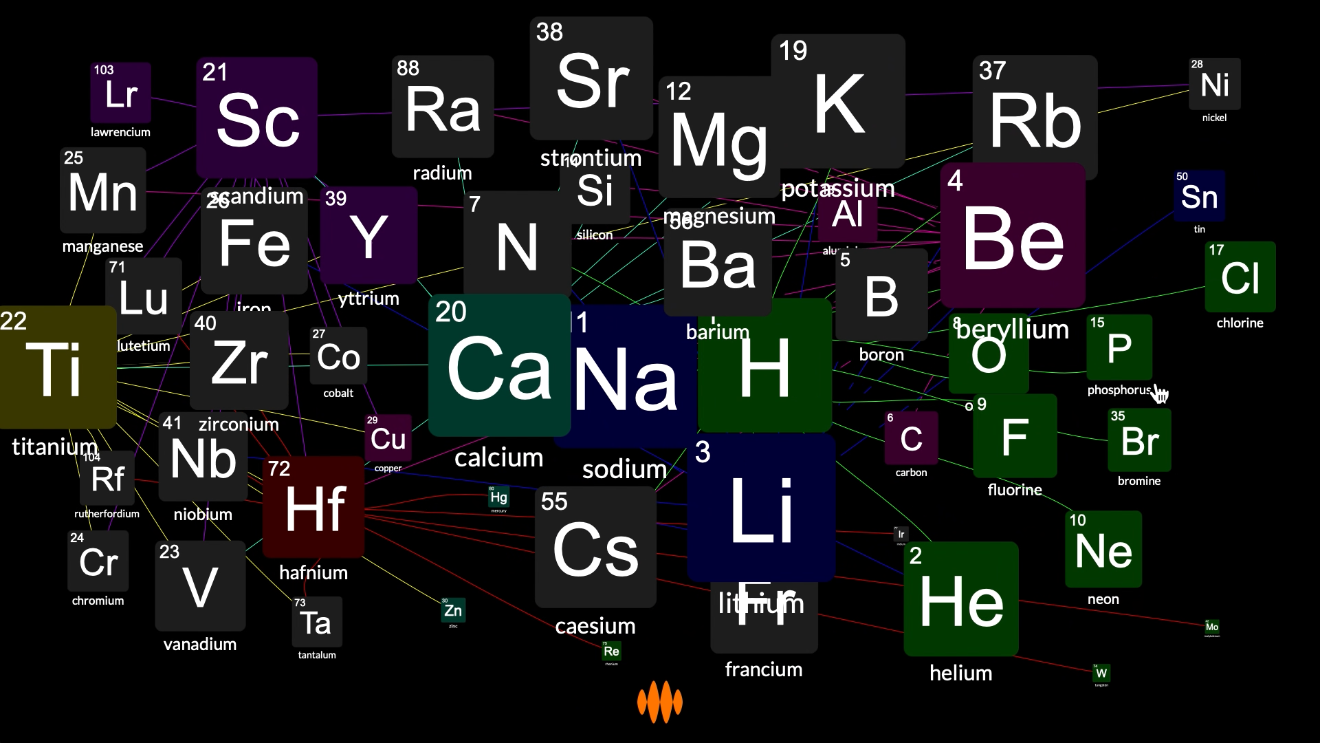

Here’s another mind, in which the nodes represent the chemical elements, and the edges connect elements according to the properties they share: properties like atomic number, thermal conductivity and abundance.

Let’s start with hydrogen, the smallest atom, with atomic number 1.

It’s closely connected to helium, of course, the next-smallest atom, with atomic number 2. But it’s also connected to the alkali metals – lithium, sodium, potassium and so on – because it’s in the same group as them, the group of atoms with a single electron in the outer shell.

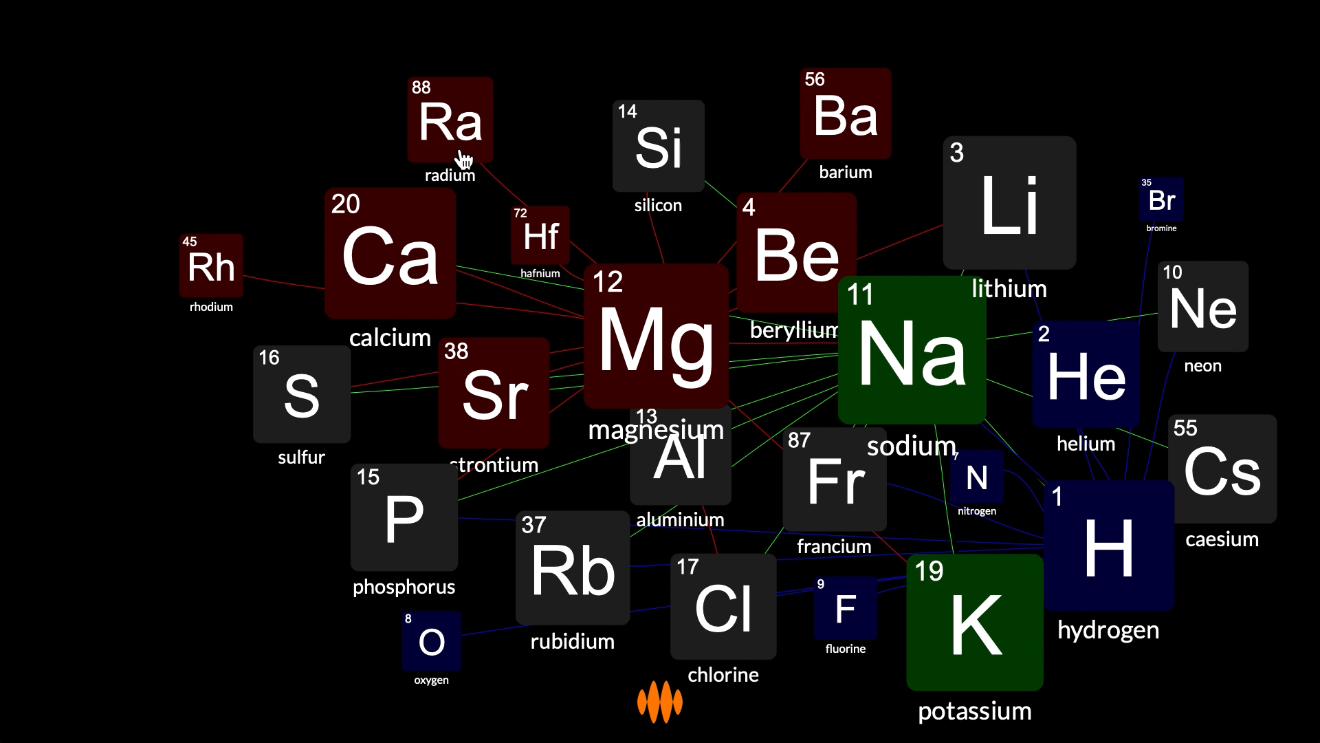

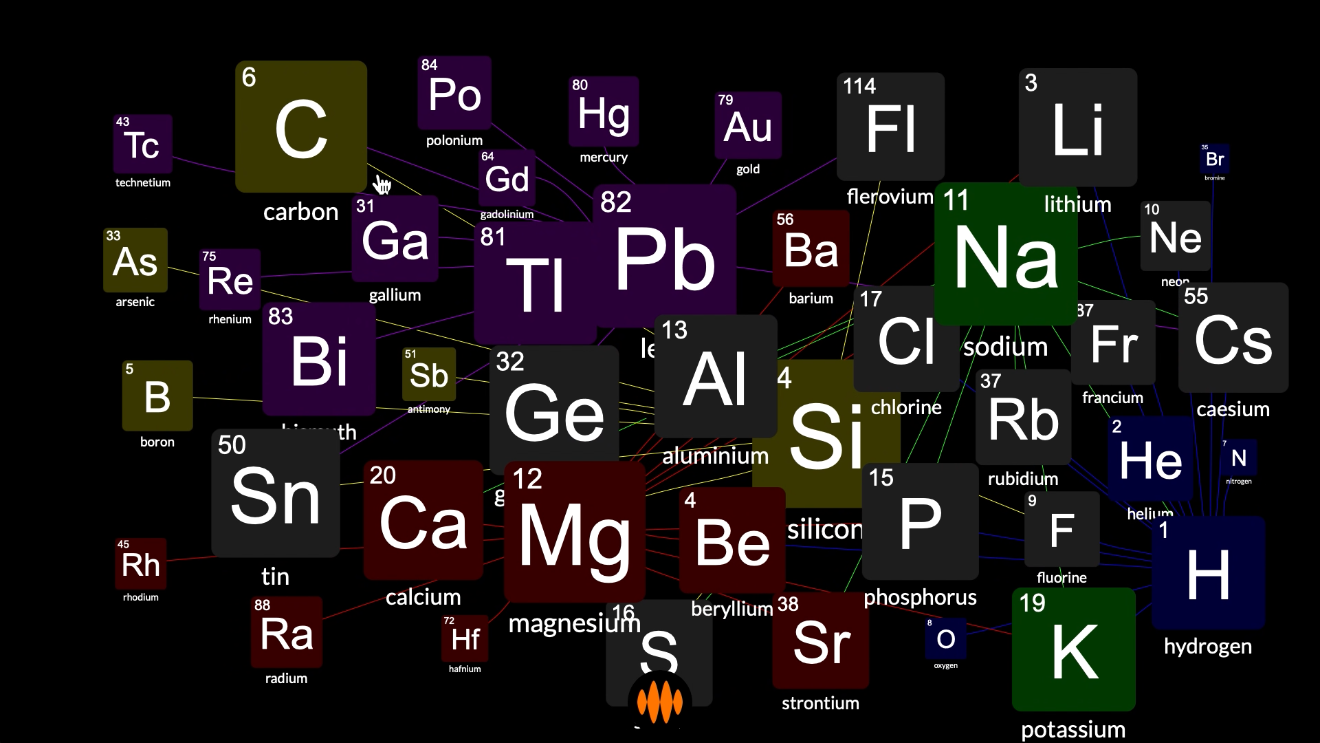

Let’s flow to sodium, then magnesium, the element next door.

We’re starting to get to less metallic elements, now, so let’s jump to silicon, the quintessential semiconductor. It’s connected to other elements that form four bonds – carbon, germanium, tin, and so on – but let’s jump to a heavier element in that group, lead.

Now we’re seeing a whole bunch of heavier elements, so let’s work our way back across the lower regions of periodic table, through mercury, gold, platinum and tungsten to hafnium.

Now let’s go lighter again: titanium, scandium, calcium, beryllium, lithium. We’ve flowed all the way around the periodic table, right back to hydrogen.

Throo the zoo

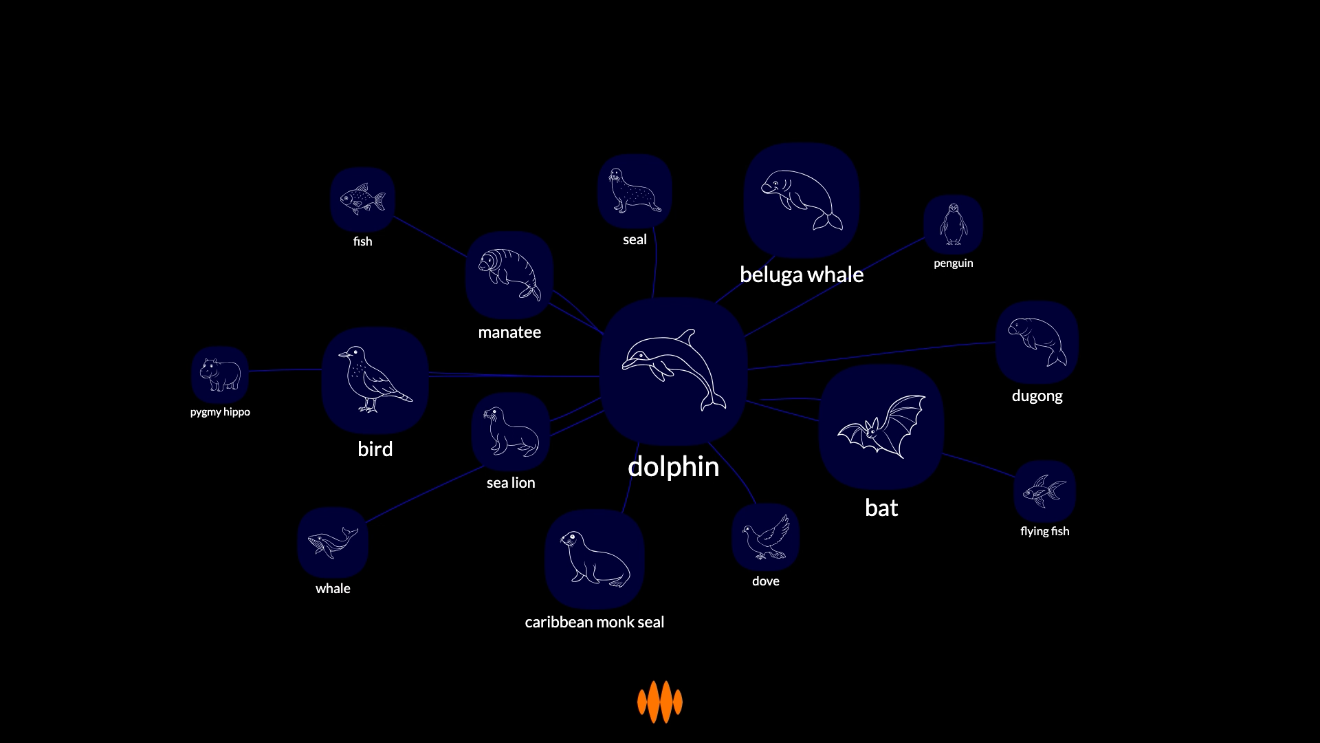

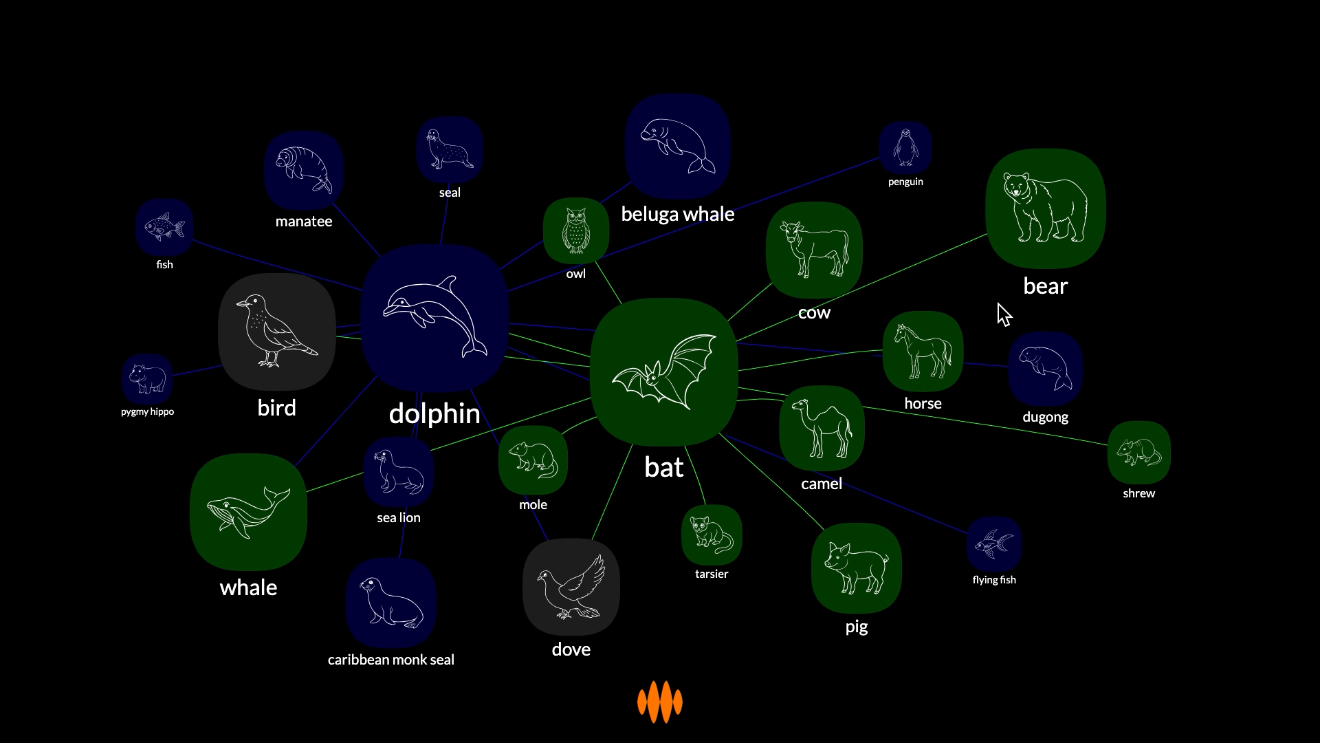

As we’ve seen, nodes in Open Web Mind can be connected by numbers, such as land border lengths and thermal conductivities. But they can be connected in other ways, too. They can be connected by non-numerical relationships, or by mere association.

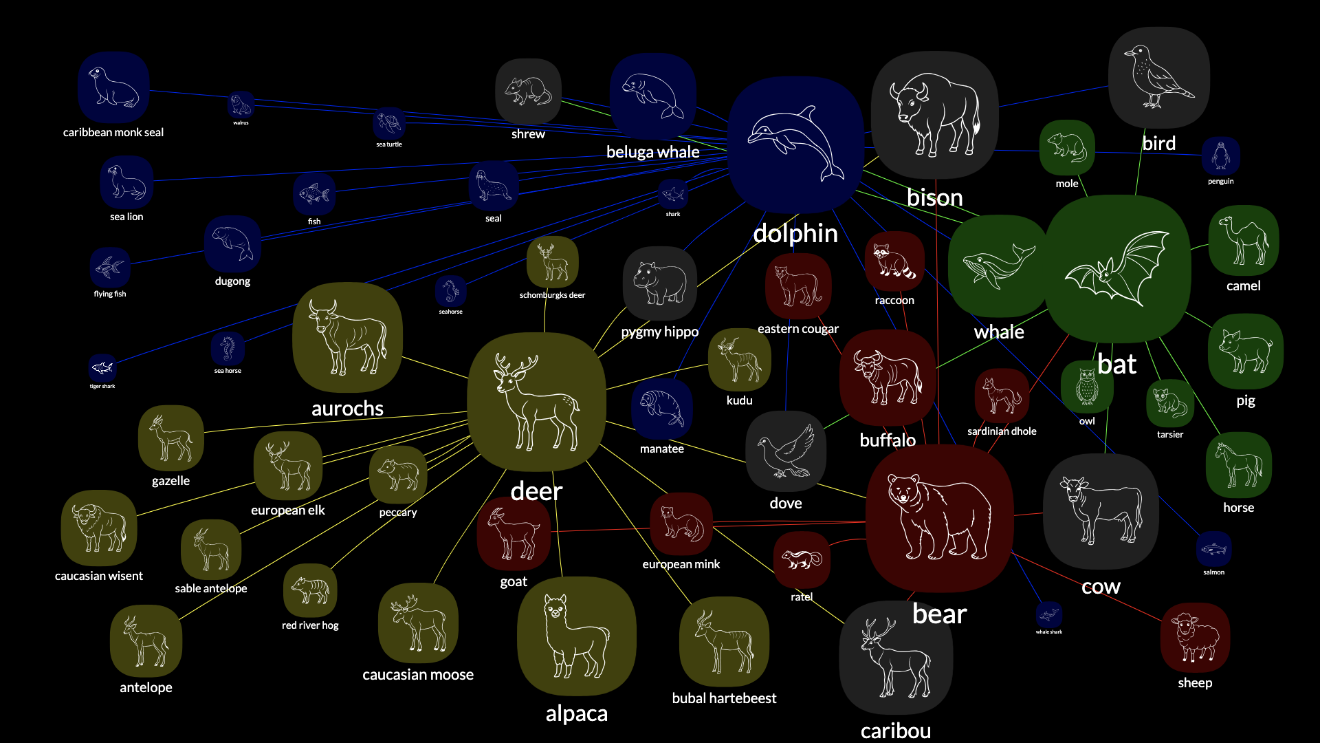

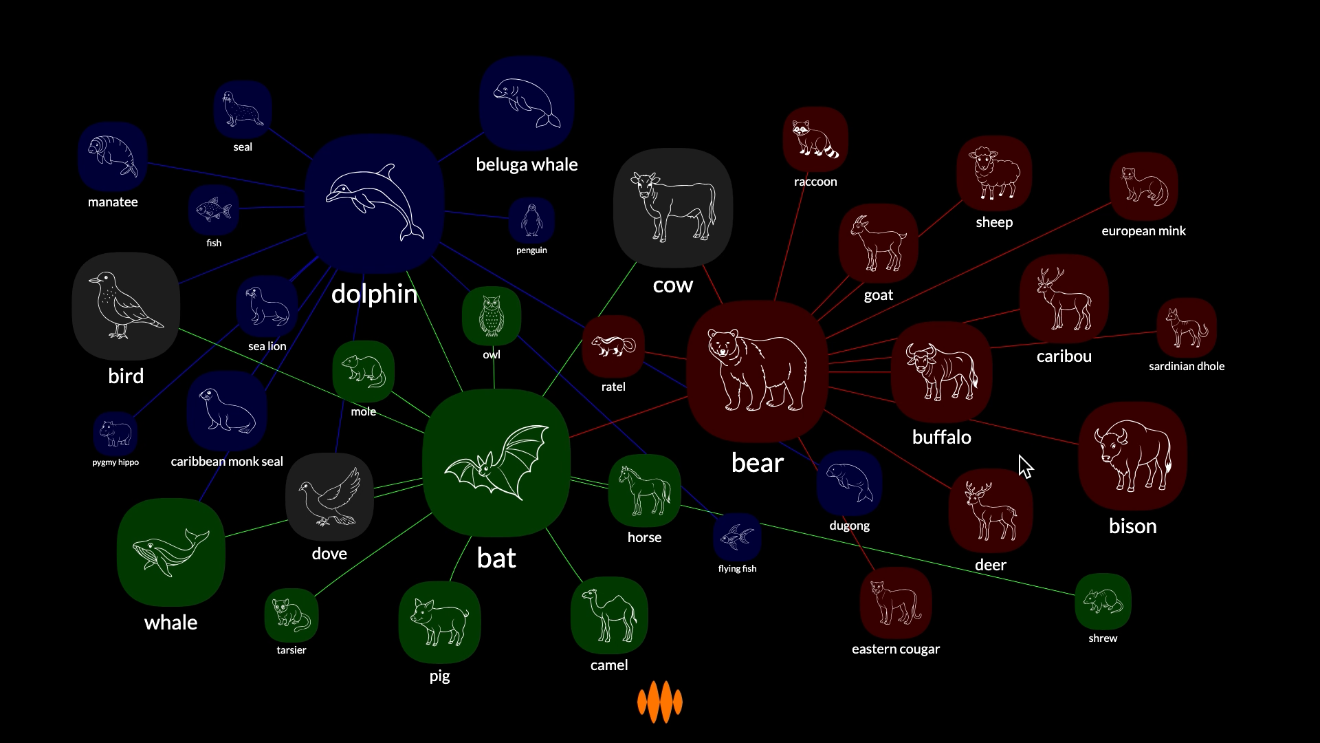

Here’s a mind in which the nodes represent animals.

I’ll start with dolphins.

I can flow anywhere from here, to animals associated with dolphins...

...through animals associated with the animals that are associated with dolphins...

...and so on.

This is smooth.

This is reflexive.

This is effortless.

This is flow.

Myriad Minds

The minds I’ve shown you – the countries mind, the chemistry mind, the animals mind – are just small, narrow minds.

With Open Web Mind, you flow through myriad minds.

You can flow through larger, wider minds, representing all human knowledge.

You can flow through your own mind, with all your own information, melded with humanity’s mind.

You’re not trapped in a one-dimensional infinite scroll determined by some algorithm.

You’re not trapped in a series of questions and questionable answers determined by some AI.

You’re free to decide your own path through the knowledge hypergraph.

As easily and expertly as the mechanic, the violinist and the skier extend flow into the wrench, the bow and the poles, Open Web Mind allows us to extend flow into our collective mind.