As I described in my article What is rank? Open Web Mind captures a core characteristic of mind, that some connections between ideas are stronger than others, by ranking these connections.

For each node, representing an idea, we simply list the edges to other nodes, representing connections with other ideas, from the strongest to the weakest.

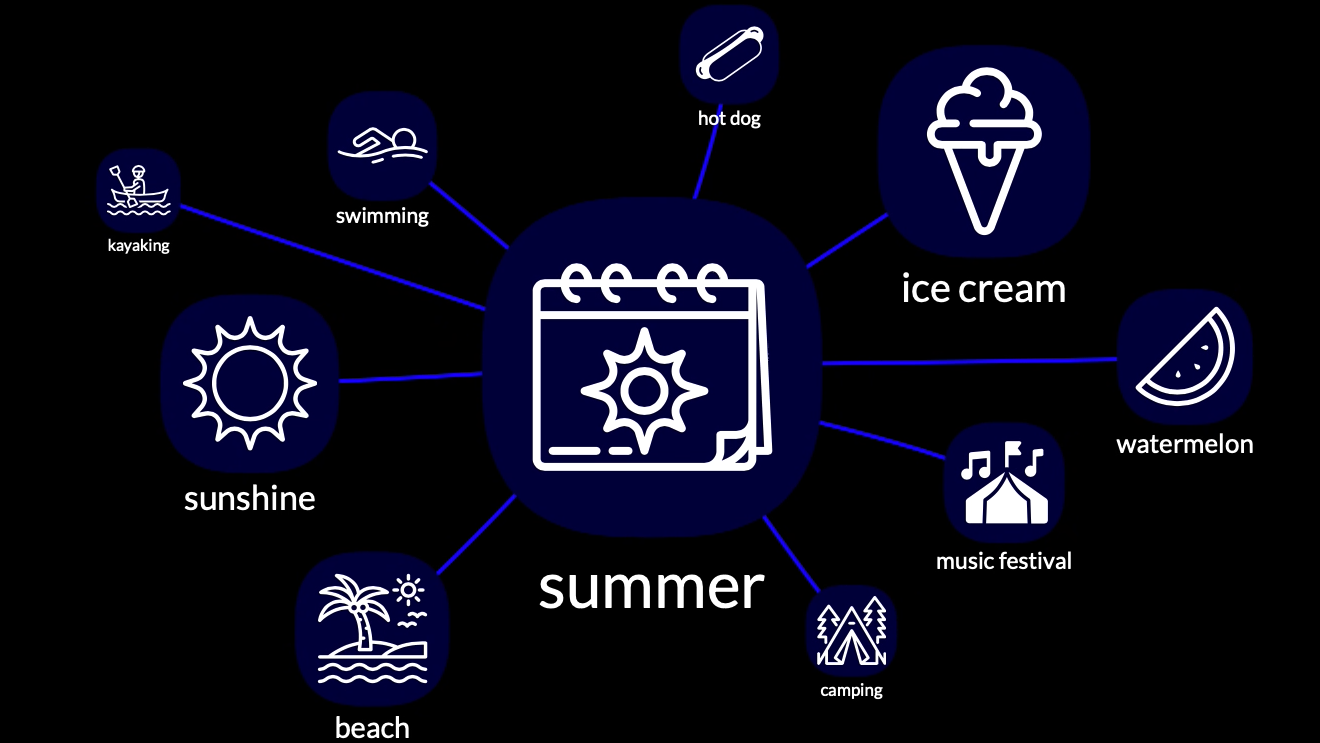

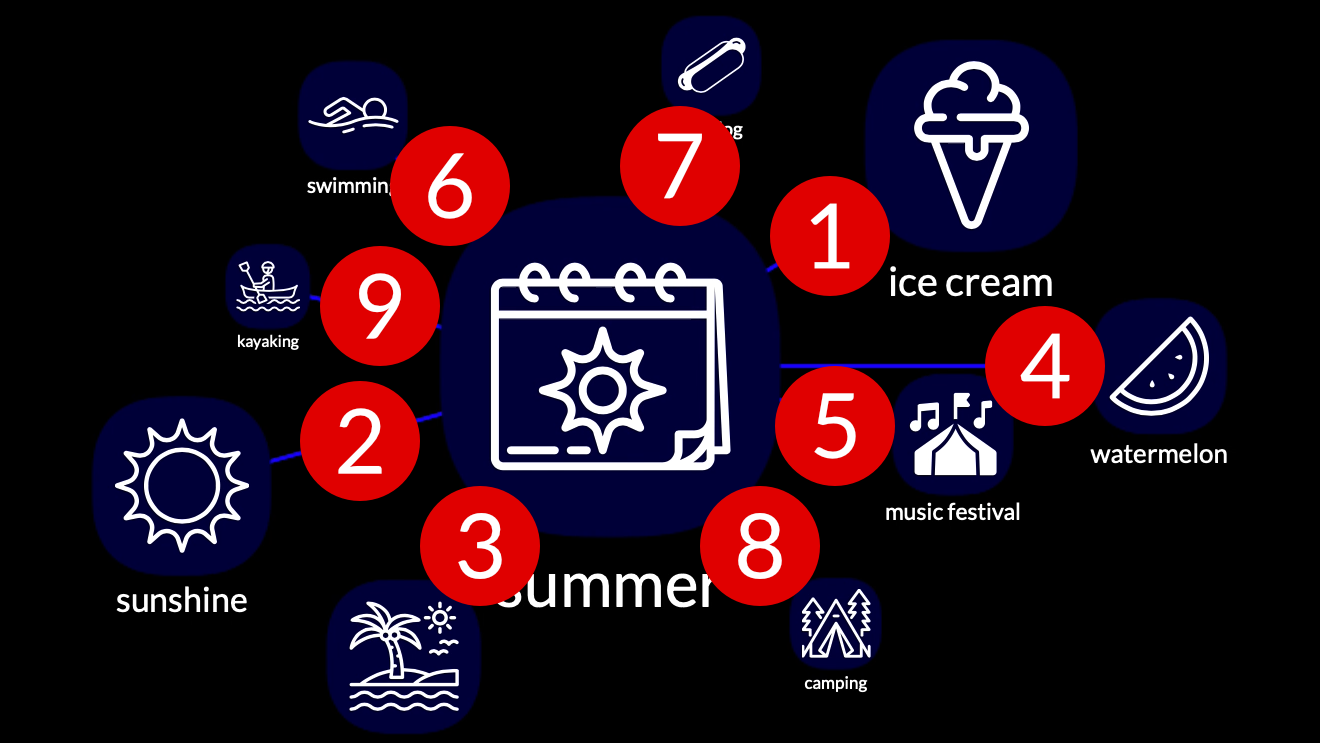

If, every time you think of summer, you think of ice cream, then the list would begin with ice cream, followed by sunshine, followed by music festivals, and so on through the list of ideas connected with summer in your mind.

To put it in terms of rank: from the node representing summer, the edge to the node representing ice cream has rank 1, the edge to the node representing sunshine has rank 2, the edge to the node representing music festivals has rank 3, and so on.

I ended that last article on a cliffhanger.

How do minds decide these rankings?

This question of how to rank edges in Open Web Mind will take us to the even deeper question of how we make connections in our minds.

How do minds rank edges?

How did your mind come to hold that the connection between summer and ice cream...

...is stronger than the connection between summer and sunshine?

Well, there’s no one answer to that question.

Open Web Mind is a protocol for free thought, and it’s a pretty light protocol.

It allows your mind to share your connections with me, and my mind to share my connections with you, but it doesn’t limit how our minds might make those connections.

So here are three answers to that question: three ways in which minds might rank the edges from a node.

Nation nodes

Let’s take a simple example.

Let’s take a limited set of nodes and edges: the nodes representing the countries of the world, and the edges representing the connections between them.

How do we rank those edges?

How do we rank the connections between one country, say India, and each of the other countries of the world?

Precision minds

Here’s one way.

Some minds are inhumanly precise.

They make connections between ideas from accurate, reliable, well-sourced data sets.

To create such a mind for the countries of the world, I used a list of ISO 3166 country codes from the International Organization for Standardization to create a node for each of the countries. Accurate, reliable, well-sourced data.

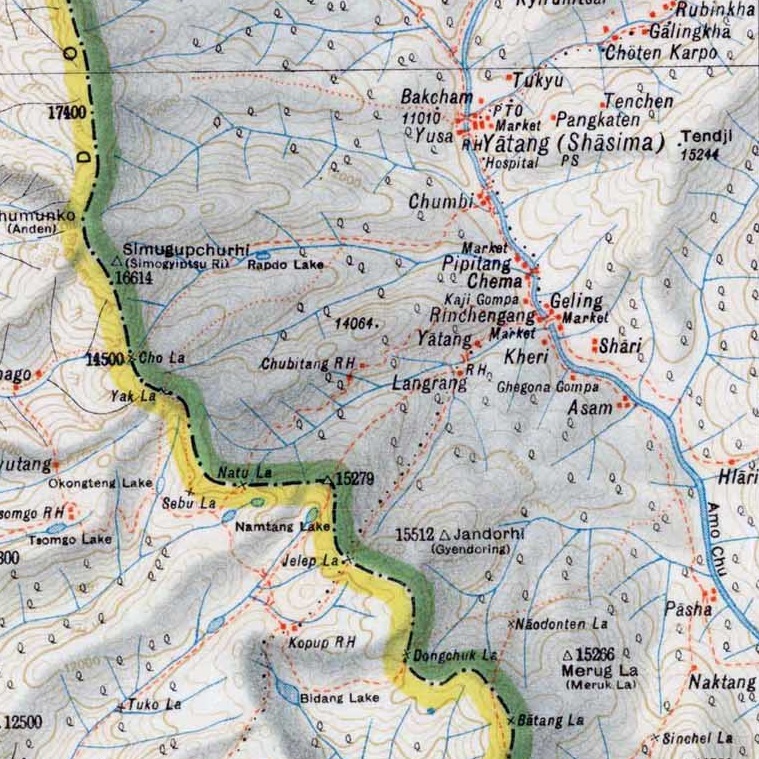

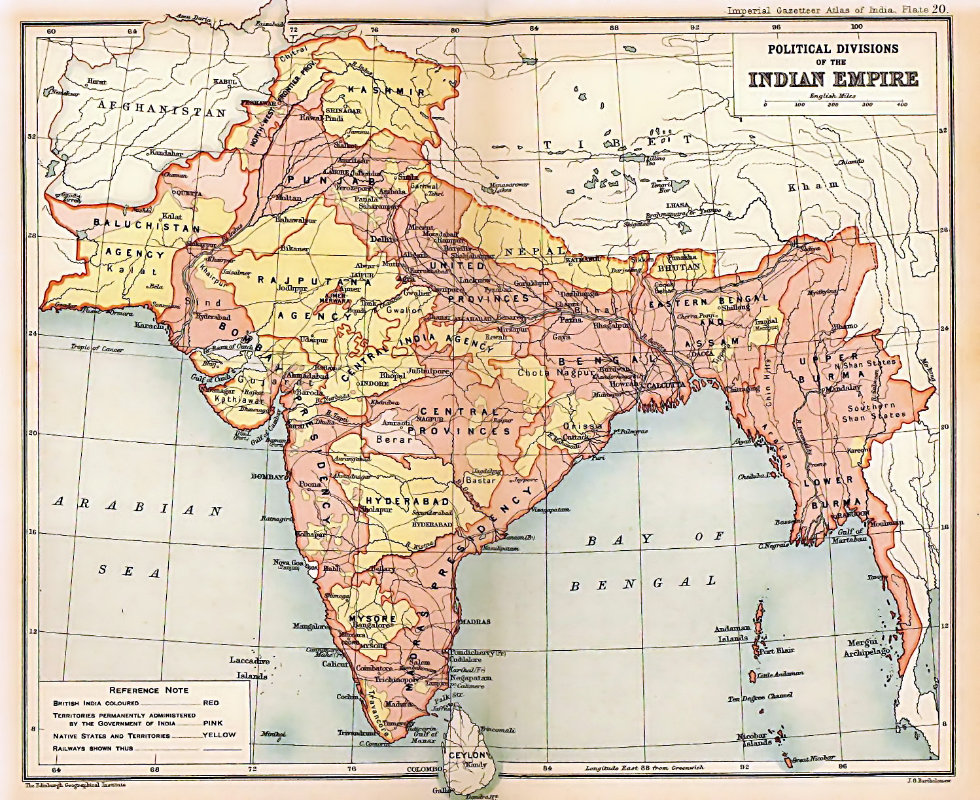

There are many ways in which I might create edges between the nodes representing the nations. One way countries are connected to other countries is physically: they share a land border. So I used a list of land boundaries from the CIA’s World Factbook to create an edge between each country and each of the other countries with which it shares a land border. Again, accurate, reliable, well-sourced data.

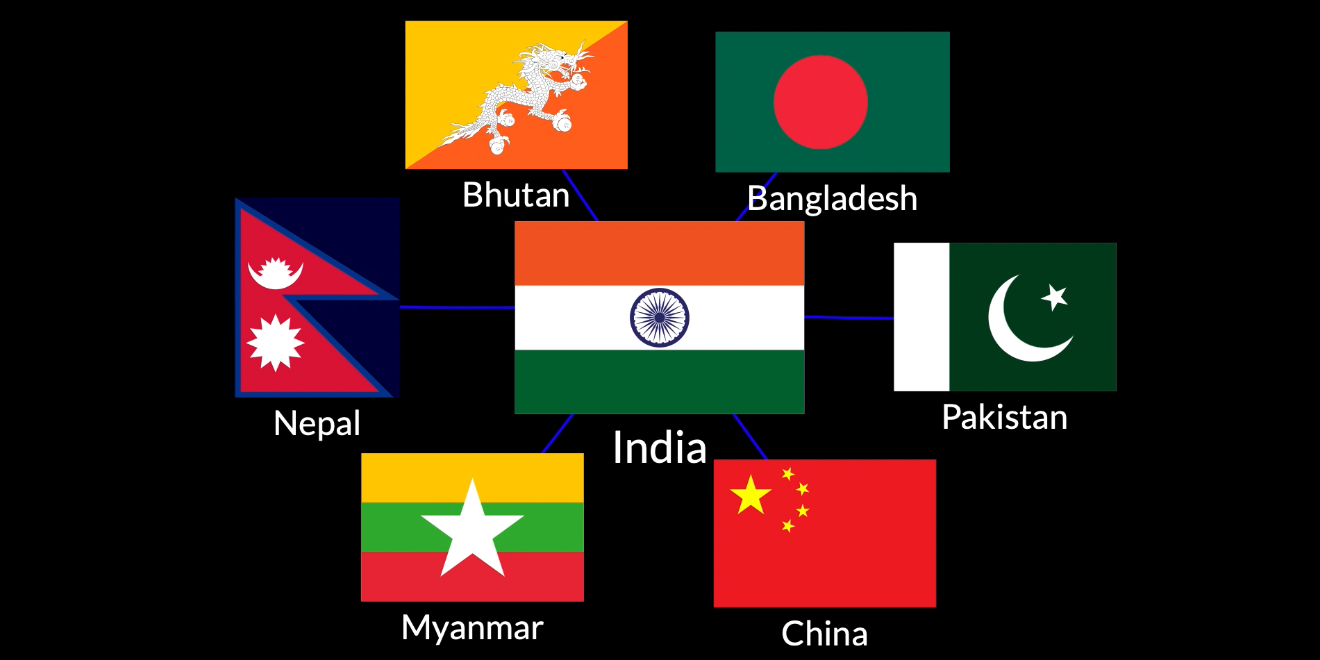

India, for example, shares land borders with Bangladesh, Bhutan, Burma, China, Nepal and Pakistan, so I created an edge between the node representing India and the node representing each of those neighbouring countries.

How did I rank these edges?

Well, for a precision mind, there’s one obvious way to do it. India’s land border with Bangladesh is 4,142 km long, while its land border with Bhutan is only 659 km long. Purely from the point of view of shared land borders, India’s connection to Bangladesh is stronger than its connection to Bhutan.

So I ranked the edges representing India’s land borders from the longest to the shortest: the edge to Bangladesh is ranked 1, the edges to Pakistan, China, Burma and Nepal are ranked 2, 3, 4 and 5, and the edge to Bhutan is ranked 6.

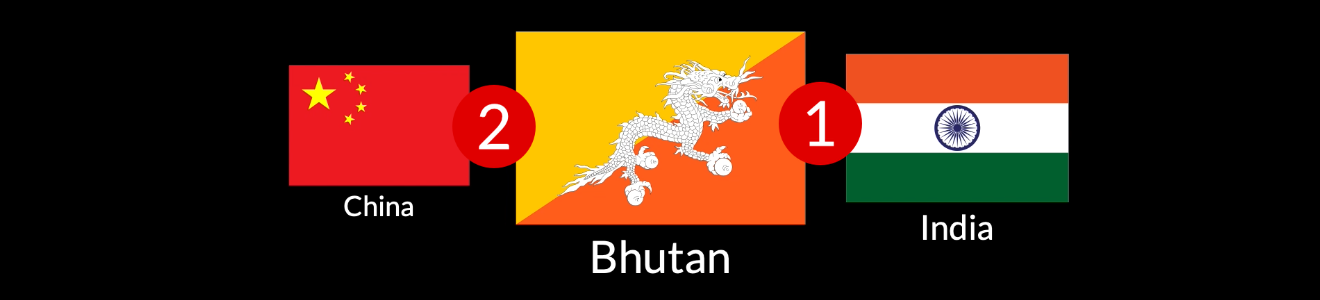

Note that these ranks, of edges from the node representing India to the nodes representing these other countries, are from India’s point of view. From the other countries’ points of view, things look different. Bhutan, for instance, has only two land borders: the 659 km border with India, and a 477 km border with China.

From India’s point of view, Bhutan’s not all that important, ranking 6th in the list of land borders, but from Bhutan’s point of view, the land border with India is its most important, ranking 1st.

Of course, land borders aren’t the only connections between countries. Countries might be connected by proximity along a maritime border, too, or by trade, or migration, or history, or culture, or political affinity, or military alliance, or in any number of other ways.

I’ll create edges for each of those connections, too, in this precision mind for the countries of the world, from similarly accurate, reliable, well-sourced data sets, and I’ll rank those edges according to similarly exact criteria.

Free-association minds

Here’s another way we might rank edges.

Some minds are rather less precise. These minds, like human minds, form free associations between ideas.

I’m creating such a mind from Wikipedia.

I started by creating a node representing the subjects of each of the articles in Wikipedia.

There’s a Wikipedia article on campanology, the science and art of bells and bellringing, so I created a node for campanology.

There’s a Wikipedia article on Tulip mania, the bubble in tulip bulb prices during the Dutch Golden Age, so I created a node for Tulip mania.

There’s a Wikipedia article on the match between Coventry City and Bristol City in 1977, which conveniently ended in a 2-all draw that allowed both teams to avoid relegation to the second division, rather inconveniently for Sunderland, the team that was relegated instead; so I created a node for that, too.

And, of course, there’s a Wikipedia article on India, so I created a node for India in the Wikipedia mind.

There’s plenty of precise data in Wikipedia that’ll make its way into this mind, but let’s focus on free association for now.

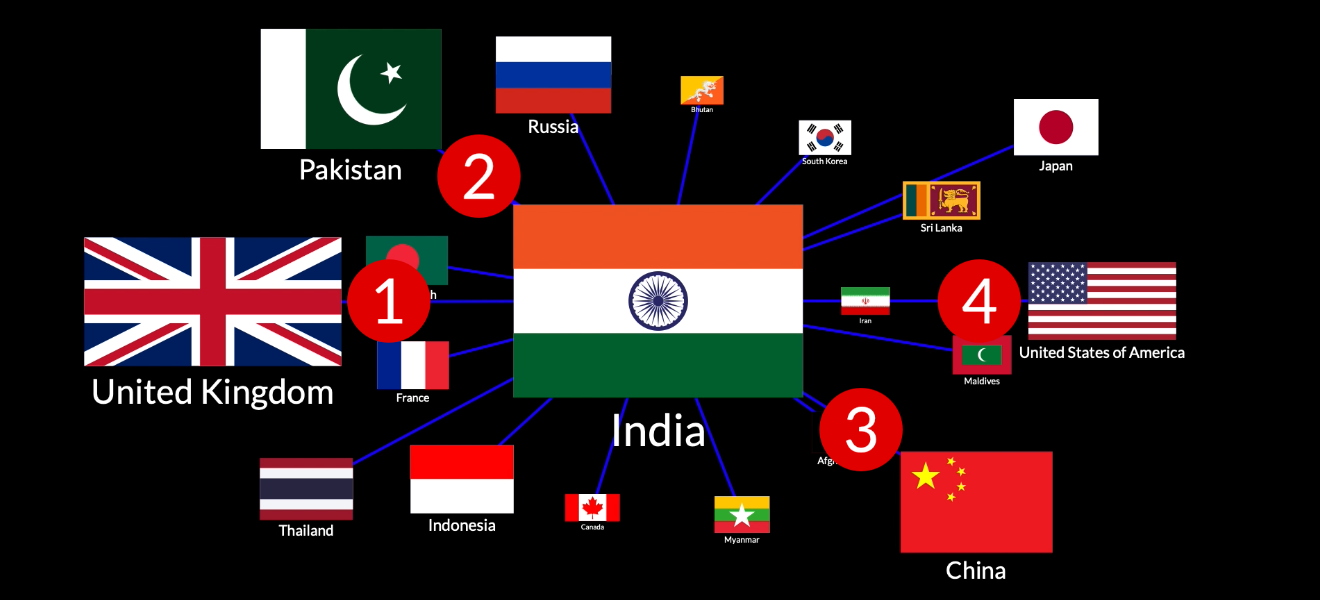

The Wikipedia article on India mentions a couple of dozen other countries, including, of course, Bangladesh, China and Pakistan.

The article describes the connections between India and these other countries. It explains, for example, that there have been a number of military conflicts between India and China across that land border they share...

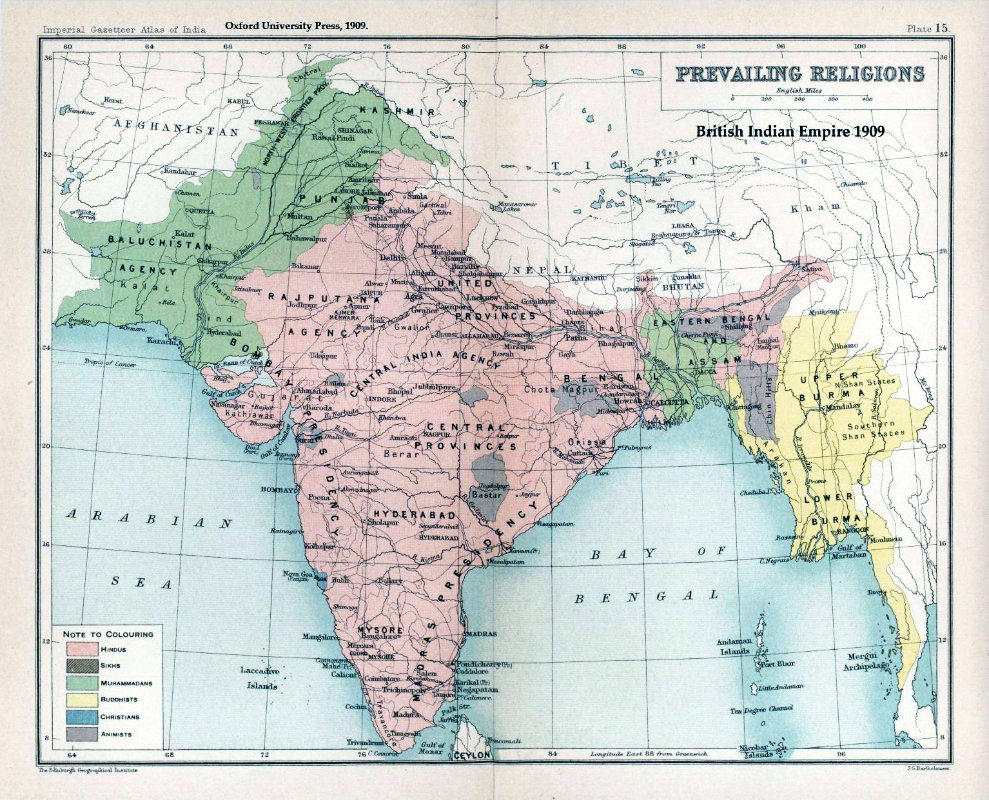

...and it describes India’s common ancestry with Pakistan and Bangladesh, through the partition of the British Indian Empire in 1947.

Focusing on free association, however, I neglected the abundance of information captured in these descriptions. Instead, I simply created an edge between the node representing India and the node representing each of the other countries mentioned in the Wikipedia article, representing an association between them.

How did I rank these edges?

Well, again, there’s one obvious way to do it. Pakistan is mentioned 29 times in the Wikipedia article on India, while China is mentioned only 24 times. So India is more strongly associated with Pakistan than with China, in Wikipedia’s mind, at least.

There are other countries mentioned in the article that don’t share a land border with India, countries that are nowhere near India. The United States, with which India co-operates economically, strategically, and militarily, is mentioned 14 times, and Britain, which has a complicated colonial history in India, is mentioned 37 times.

So I ranked the associative edges between India and these other countries in the Wikipedia mind from those with the most mentions to those with the least: the associative edge to Britain is ranked 1, and the associative edges to Pakistan, China and the United States are ranked 2, 3 and 4. Once again, Bhutan appears towards the end of the list.

This associative way I used to rank edges in the Wikipedia mind is very different from the precise, data-driven way I used to rank edges in the mind for the countries of the world.

It may be less precise, but it’s much closer to the way we form connections in the human mind. When I think of India, I think of Pakistan, not because I know the precise length of the 3,190 km land border between the two countries, but because I’m so used to thinking of India and Pakistan in the same moment: every time I look at a map of the world, India and Pakistan are right there next to each other...

...every time I think of the partition of the British Indian Empire, India and Pakistan are right there next to each other...

...every time I think of the best curries in the world, India and Pakistan are right there next to each other.

There’s a place for precision in our minds, but there’s a place for free association, too.

Thought follows thought

And so to a final way we might rank edges.

Initially, this way will have less of an impact, but ultimately, as more and more thinkers are active on Open Web Mind, it will have the most impact.

In the human brain, the more often a pathway between neurons is activated, the stronger that pathway becomes, which makes it more likely to be activated in the future.

If, every time you heard about India in the past, you heard about Pakistan in the next moment, then every time you think about India in the future, you’re likely to think about Pakistan in the next moment.

That’s an oversimplification of the complexity of the human brain, but it’s a powerful oversimplification.

It’ll be extraordinarily powerful in Open Web Mind.

Initially, when thinkers on Open Web Mind, in their explorations of human knowledge, arrive at the node for India, they’ll be able to flow to related nodes along edges that have been been ranked in a precise, data-driven way by precision minds, or in a freer, associative way by free-association minds.

But the more I think about India on Open Web Mind, the more I flow to the ideas connected with India that are important to me, and the more these connections will be reinforced in my mind.

If, every time I arrive at the node for India, I flow not to the node for Pakistan, but to the node for Varanasi, remembering the mists over the Ganges, then the edge to the node for Varanasi will end up with a higher rank in my mind than the edge to the node for Pakistan.

And the more you think about India on Open Web Mind, the more you flow to the ideas connected with India that are important to you, and the more those connections will be reinforced in your mind.

If, every time you arrive at the node for India, you flow not to the node for Pakistan, but to the node for cricket, in honour of the countless India test matches you’ve followed, then the edge to the node for cricket will end up with a higher rank in your mind than the edge to the node for Pakistan.

Our minds are plastic.

They’re formed by our thinking.

My mind is formed by my thinking.

Your mind is formed by your thinking.

Humanity’s mind is formed by humanity’s thinking.

And that, ultimately, is how we’ll rank edges in Open Web Mind.